What is it like to work as a music manager in Ukraine despite all the challenges? And what do European colleagues have in common

The Ukrainian music market is relatively young compared to the European one. And the full-scale war in the country has significantly complicated its development.

Despite this, Ukrainian music managers observe similar trends on the European scene. And they know exactly what approach of their foreign colleagues they want to see in the Ukrainian music market.

We spoke about this with five participants of Digital Labs: music managers. Among them were Kateryna Dubovyk, a manager of Hate Speech band; Anatolii Kyselov, a manager, co-author and guitarist of the Illusion of Silence band; Natalia Vasylieva, a manager of the ethnomusical band BarabanZA; Solomiia Hrebeniak-Dubova, a manager and member of the family ethnoband ZERNO; and Liliia Lazarieva, a cultural manager and co-founder of the CTS Records label.

What is the path of a music manager in Ukraine from your experience?

For me, this was my first experience of being involved in the inner workings of a festival. And it was not only about music, but also about social initiatives. That’s how I became drawn to this field.

In art, what matters most to me is being relevant. Unfortunately, for us, that relevance is about war.

Anatolii Kyselov: I have been involved in music since childhood—about 20 years—but I gained management experience from another field: organising dental forums.

When, after the full-scale invasion, we decided to reformat Iliuziia Tyshi into something more professional, it became clear that someone had to manage it all. And it was best that it be someone within the band who understood its needs. Given my background, I took on this role.

Natalia Vasylieva: I don’t think there is a set path into music, especially when it comes to the ethnic niche. For instance, I am a mathematician by training. I came into music consciously at the age of 30.

Together with my husband, Denys Vasyliev, we founded the ethnomusic club BarabanZA—a space for collective jams, drum lessons, and warm gatherings of like-minded people. The community grew, and over time, we became a fully-fledged stage project. Invitations to perform soon followed.

While Denys focused more on the musical side, I took on the management. At the same time, I remain a musician in the band: I play several instruments, teach frame drums, and compose.

Performance of BarabanZA band. Credit: Ellen Schmauss

Solomiia Hrebeniak-Dubova: Since we created the band with my sisters, as the eldest, I naturally assumed the managerial role. I already had good experience in this area.

At some point, however, I felt I lacked specific skills in managing musical groups. I needed to understand how everything functions from the inside—copyright, communication, working with labels and distributors. Then I came across Digital Labs, which answered all these questions.

What challenges and difficulties does a music manager face in Ukraine?

Kateryna Dubovyk: First of all, security. I began organising events after the full-scale invasion and thought, “Well, what problems could people have had before?” When your event, with a budget of one and a half million, is cancelled due to a missile threat, and you have no control over it. All you can do is accept it and take the risk.

The next challenge is linked to mobilisation. The members of Hate Speech are mostly young men. Our lead singer is already in the army.

It is important for us that both the music the band releases and the concerts carry meaning. That meaning is helping the army, so we invest most of our income there. One hundred per cent of the earnings cannot go into the band’s existence when the very existence of the country is at stake.

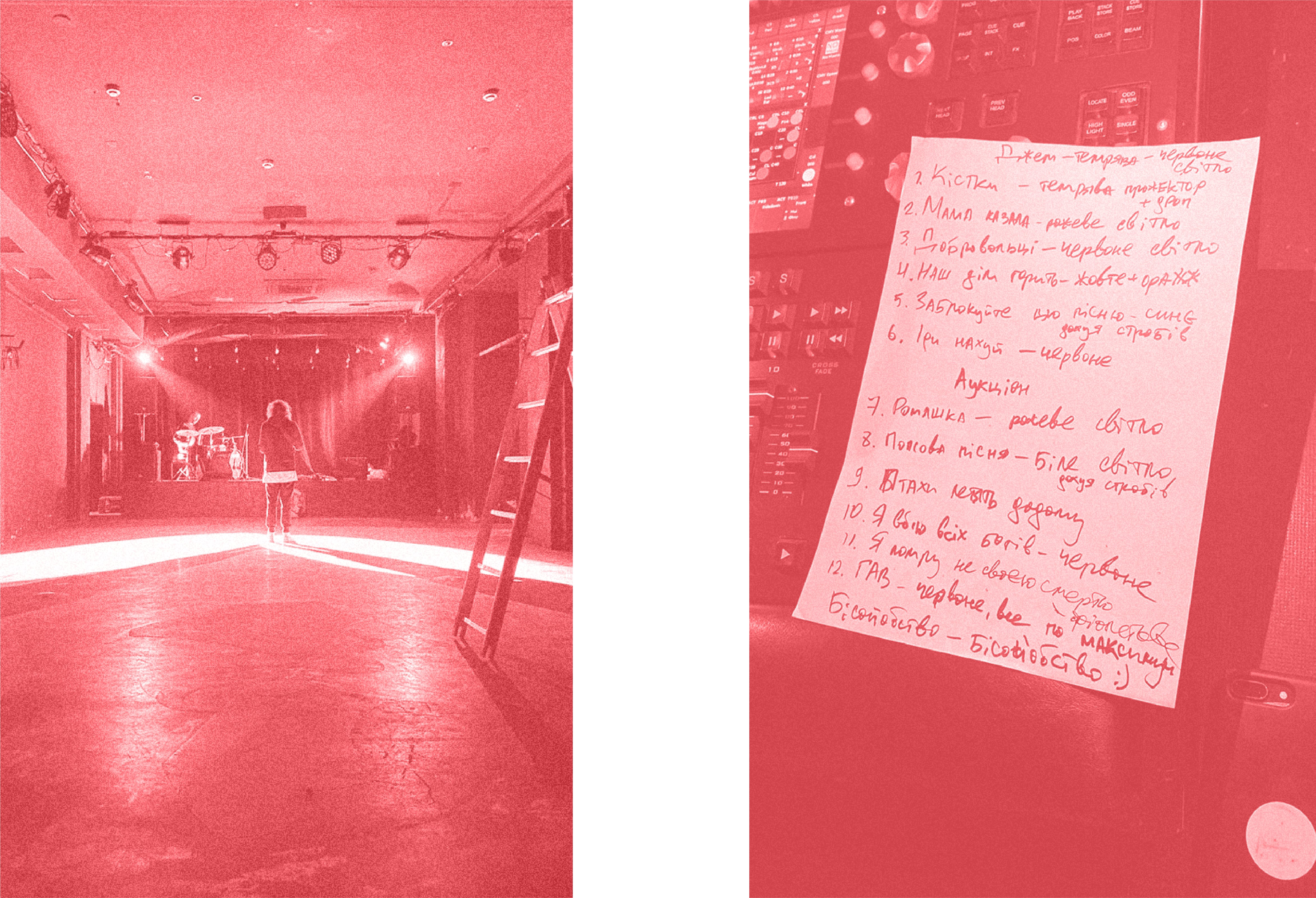

The Illusion of Silence band

Anatolii Kyselov: In Ukraine, it is hard for newcomers to get on radio and television. Despite having a sufficient number of videos and songs, we have encountered this ourselves.

Why is that? I think it is due to the established ecosystem of modern media, where new independent performers are not particularly welcome. At least, that is how it seems to me.

On the other hand, there is a completely different approach in programmes such as Digital Labs. Thanks to this, I now see opportunities for the band’s development and for concerts in Europe.

Natalia Vasylieva: One of the most tangible challenges is logistics. There are more than 12 members in the band, and when we need to go to a concert or festival, organising the trip becomes a separate mini-project. It means transporting not only people but also a considerable number of large musical instruments.

The next challenge is financing those trips. If these are foreign performances, I prepare grant applications, look for partners, and apply to mobility programmes for support.

Another important factor is communication within the team. We are an amateur group. People remain not because of the fees, but because the work inspires them, gives them support and meaning. For me as a manager, it is crucial that the band stays alive and motivated. This is our main resource.

How is the work of a music manager different in Ukraine and abroad?

Kateryna Dubovyk: When planning a tour in Ukraine, you may encounter certain restrictions. You move according to what the listening statistics suggest. Besides, some cities are frightening to visit with a festival.

In Europe, there is a wider choice and audience. You can tour capitals and developed cities. If borders were easier to cross now, we would be exploring the foreign market as well.

Anatolii Kyselov: In Europe, if a band does not have a music manager, no one will work with them. There has to be a specific person responsible for everything. In Ukraine, it still feels as though people do not fully understand why a music manager is necessary.

Our market lacks a proper business component. I once heard a brilliant phrase: show business is both a show and a business. And if there is no business, there will be no show. Otherwise, there will be no money for the band’s development, and no one will listen to it.

The backstage of Hate Speech band

Ethnoband ZERNO, which preserves the tradition of conducting haivky (traditional spring folk songs)

Solomiia Hrebeniak-Dubova: In Europe, intellectual property is taken far more seriously. You can live from your creativity, receive royalties, and control where your music is used.

In Ukraine, by contrast, some people still claim that creativity should not cost money at all—that it is an educational product to which everyone ought to have access.

Liliia Lazarieva: The music industry abroad has a long history. For example, publishing in the UK has existed for over 150 years. Some well-known labels have been in the market for a hundred years. Unfortunately, the Soviet Union did not allow the music business to develop in Ukraine.

Electronic music of non-academic genres in Europe and the United States has developed naturally since the second half of the 20th century. In our country, it only appeared after the fall of the Iron Curtain, in the mid-1990s. Professional management in this area therefore only began forming in the early 2000s.

Even now, during the war, it is hard for European colleagues to imagine how we continue to work here.

What lectures from European colleagues do you remember the most?

Kateryna Dubovyk: At a lecture on production, Björn Köhler [director of independent labels BlueCat Music and FunStation] said that this field no longer works as it used to, but how it works now is still unclear. Entering the market has become cheaper and easier for artists in some places. This confirmed my assumptions about working with labels. Interestingly, this is a trend not only here but also in Europe.

The shooting of the video clip for the Illustion of Silence band

Solomiia Hrebeniak-Dubova: The first thing the project helped me with was understanding copyright and how to protect my music.

Consulting with Björn was very valuable, covering the band’s identity, positioning, logo, and necessary changes. I now know what I will be working on in the near future. We need to distribute roles within the team and discuss the direction of our development.

Overall, the lab gave me more confidence in our product. Although we are not yet ready to turn the project into a business model, I now understand the steps required to do so.

Liliia Lazarieva: It was particularly interesting to analyse case studies about local projects. I remember the story of the band KRAFTKLUB from the small East German town of Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz), which Björn shared with us. How the musicians entered the market without a large budget, how they presented themselves, and why it succeeded.

The story of the KRAFTKLUB video for the song “I Don’t Want to Go to Berlin” resonated with me. It featured footage of a large portrait of Marx being removed from a building—a symbol of farewell to the Soviet Union. In Ukraine, we went through a similar process of de-communisation.

Text: Kateryna Amelyna

Editing: Viktoriia Osipova

Translation into English: Iryna Goyal