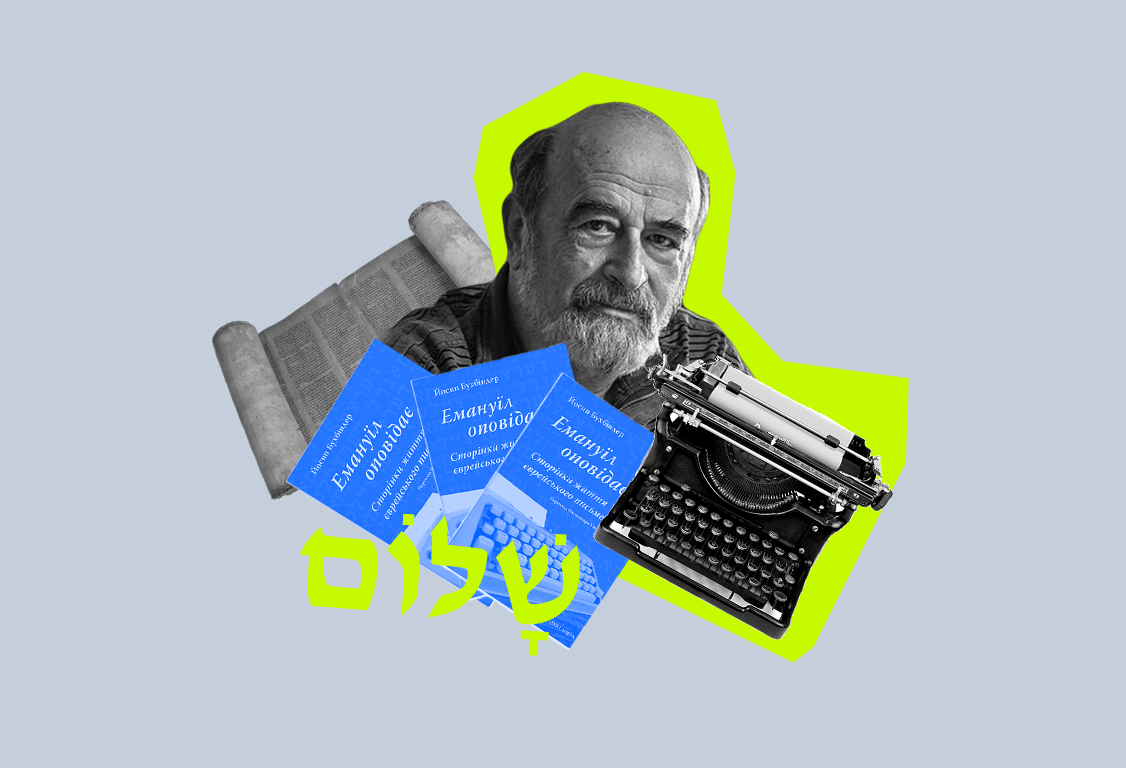

Jewish literature in Ukrainian: an interview with Leonid Finberg about translations from Yiddish and Hebrew

There are almost no Yiddish-speaking communities left in modern Europe. To preserve the lost cultural heritage, the Centre for the Study of Jewish History and Culture has been translating literature from Yiddish and Hebrew into Ukrainian for more than 15 years.

The memoirs of Joseph Buchbinder, translated and published with our support, are just one example. We spoke with Leonid Finberg, head of the centre, about the preservation of Jewish cultural heritage, the enrichment of Ukrainian literature, and modern publishing realities.

Today, we have eight translators who have about 10 years of translation experience from these languages. Oddly enough, we have more Yiddish translators than Hebrew translators. Almost all of them studied at the Magisterium in Judaica at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, where the Yiddish course is mandatory.

We have already published five translations from Yiddish and Hebrew together with the Dukh i Litera publishing house. We are also working on a large-scale project with the support of Creative Europe, where we plan to publish seven more translations. This is a breakthrough for us because no other country in Eastern Europe has such a large Yiddish translation project.

Research work and new publications

Since the 1990s, we have started collecting archives of Jewish writers. The works of those who survived the Holocaust and the Gulag — and this was the path for almost all of them — are in our archives today in one way or another. For the most part, these archives were shared with us by their children, because practically none of them knew Yiddish. In the post-war years, for speaking Yiddish one could be accused of Zionism, nationalism, and anything else, so parents were afraid to even teach their children the native language. Currently, we have about 15 individual archives: some are very large, over 100 folders, and some are a smaller, three to five. This is one of the largest collections of Yiddish literature, correspondence, and history of activity of Jewish writers of the post-war period. Some time ago, we started translating these texts, because they are extremely interesting.

Among our archives is the archive of Joseph Buchbinder. I had the pleasure to know him personally in the last years of his life, although I cannot say that we communicated closely. We recorded the memories of his daughter, who gave us the archive. Among the numerous letters and poems was a manuscript that we translated. When we were choosing what to print, we settled on a semi-documentary novel, the author’s testimony about the Gulag. I do not know of similar testimonies written in Yiddish. When we translated it, it became obvious that the choice was correct.

Not many writers, after they survived the tragedies of the Holocaust, the Gulag and the poisoning by socialist realism in Soviet times, were able to raise their heads again. Buchbinder’s book is one of the few examples where the writer was able to find the strength to write a memoir. Many Soviet writers, having gone through the horrors of the Gulag, did not return to creative work. Describing this experience is like reliving the tragic pages of the past. The merit of many of them is that they became teachers and mentors of the next generations. In Ukrainian culture, such examples are Maksym Rylskyi and Mykola Bazhan.

Jewish literature in Ukrainian translations

Jewish culture, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was one of the most interesting in the world. This is evidenced by the fact that two Jewish writers — Yosef Agnon and Isaac Bashevis Singer — were awarded Nobel Prizes in literature. It is important for us to present this cultural heritage in Ukrainian translations.

Unfortunately, we have almost no competitors in this field. Other publishing houses have published one, two, five or ten books on Jewish topics, and we have published 150 books. These are anthologies of Jewish literature from Central and Eastern Europe, books on the history of Jews (both in Ukraine and the world), as well as many translations of fiction. One of the most important books for us is “Jewish Civilization. The Oxford Textbook of Judaica.” There are also our two textbooks recommended for gymnasiums by the Ministry of Education: one on the Jewish history of Ukraine, and the other one on the Jewish art of Ukraine.

We recently closed the exhibition under the modest name “1001 books of the publishing house ‘Dukh i Litera’,” which lasted for two months at the Museum of Books and Printing of Ukraine. This exhibition was a great discovery even for us. We knew every book there, but when we saw hundreds and hundreds of books presented in the exposition in a large panorama, it made an impression on everyone.

Plans for the future

Jewish literature has hundreds of names. Of course, we would like to translate many of them. However, due to understandable financial constraints, we are unable to present books by most authors. So we chose a slightly different path. We prepare anthologies.

In the already mentioned anthology of Jewish literature from Eastern and Central Europe, there are texts by Bruno Schultz, Isaac Babel, Yosef Agnon, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. We also published an anthology of American Jewish literature with works by Abraham Cahan, Anzia Yezierska, Saul Bellow, and Philip Roth. A book dedicated to the Jewish theme in Ukrainian literature, compiled by researcher Khrystyna Semeryn, is also in the process of preparation. We hope to publish this book by autumn.

Another important publication for us, on which we are working, is the dialogues of Ukrainian and Jewish dissidents in the Gulag because our archive contains a lot of materials on this topic. We also plan to publish an anthology of contemporary Yiddish poetry shortly. In addition, an important project for us is the “library of war,” where several books about the Second World War and the present have already been published, and about ten more books are being prepared for publication.

Once a journalist asked Kostiantyn Sihov, the director of the “Dukh s Litera” publishing house, and me, how we choose books for printing. We answered half-jokingly, that usually, I name one Nobel laureate, and Kostiantyn names the other one, and then we choose who to translate first. In fact, we are working quite actively. Last year alone, “Dukh i Litera” published about 60 books. In my business journal, I have a list of publications we’re working on. And this is more than 80 books this year. This does not mean that all of them will be published, but we will definitely manage 50–60.

Institutional support

All over the world, the books we publish are not-for-profit. They are generally funded by universities. Scientists who are in charge of preparing such books do not think about where to find funds for them. Our situation is different, but we have learned how to find money to publish books all over the world. In particular, we appeal to the embassies and special institutions of various countries that are engaged in the support and popularization of cultural heritage. We have particularly fruitful relations with the House of Europe, the Polish Institute, the French Institute, the Goethe Institute, and the American Embassy. Thanks to the Book Institute, we were able to publish translations of several of our books abroad. Of course, there are private patrons in Ukraine who support our initiatives in one way or another. Proportionately, this is not a large share, but these are generous contributions, considering that these people do not have millions.

When the full-scale Russian invasion of the territory of Ukraine began, many foundations supported us, thanks to which we survived. Today, Ukrainian publishing structures are experiencing a renaissance. Kilometres-long queues at the Book Arsenal festival are just one of the testimonies. Despite the full-scale war, surprisingly, the number of books bought in Ukraine does not decrease but increases. This is still not much compared to countries with much longer publishing traditions. Nevertheless, we should not compare ourselves with others but rather with what we had yesterday. Even 15–20 years ago, we could count publications on philosophy, history or cultural studies in Ukrainian on fingers. Today it is quite a powerful market because the book plays an important stabilizing role in this crazy war situation.

Text: Nadiia Chervinska

Editing: Viktoriia Osipova

Translation into English: Irina Goyal

Photo: Duh i Litera